The White Paper: Preserving Our Public Mission through a New Partnership with the State

NOTE TO READERS FROM PRESIDENT RICHARD LARIVIERE

Many states across America, including Oregon, are struggling with the current higher education paradox—a broad consensus, fueled by the lessons of our own history, that postsecondary opportunity is critical to our collective prosperity, but challenged to sustain the investments needed in public higher education to support such prosperity. As a result of this paradox, state policies have been adopted across the United States that have fundamentally restructured public higher education systems as states and their public institutions negotiate a new balance of autonomy and accountability. In his book The Future of Higher Education: Rhetoric, Reality, and Risks of the Market, the late higher education scholar Frank Newman, PhD, notes that new policies—including public corporations, charter colleges, and measures granting increased operating flexibility and autonomy to colleges and universities—have been adopted across the country (Newman, Couturier, and Scurry, 2004). These policy debates have been driven by a variety of factors, including shifts in the revenue streams of public colleges and universities, in state socioeconomic climates, and in political philosophies that emphasize the use of the market as a regulatory framework. New state policies relating to higher education governance and reform continue to emerge across the United States. According to the research of Michael McLendon, PhD, regarding higher education governance reform, between 1985 and 2002 state governments considered more than 100 measures to modify their higher education governance systems (McLendon, 2003). Given accelerating demands for institutional restructuring and increased legislative attention to higher education public policy, the issue of how to preserve the public mission of America’s great public higher education system is at the forefront of policy discussions in states across the country—including Oregon.

In Oregon, there is growing consensus that the state must move aggressively to enact real reform that supports our collective goal to help more Oregonians earn college degrees—reform that fundamentally changes the state’s role so that each institution is better able to fulfill its public mission through increased autonomy and greater accountability to meet the state’s needs.

At the conclusion of the 2009 legislative session, Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski convened a committee called the “Governor’s Reset Cabinet.” The group was charged with examining state policies governing Oregon’s public institutions including higher education. Oregon business groups and public affairs councils including the Oregon Business Council, the Oregon Business Association, and other prominent state and regional groups routinely identify Oregon’s educational system as a top policy priority for elected officials. Meeting the educational needs of Oregonians also continues to be a point of emphasis for members of the Oregon Legislature and an increasingly more prominent discussion among candidates for governor.

The opportunity and obligation to stabilize Oregon’s public institutions of higher education is also top of mind for my presidential colleagues and me in the state system. Late last year, I joined my presidential colleagues in agreeing to a set of principles to guide our thinking about these critical policy issues. The chancellor and each of the individual presidents have made compelling arguments for a change in relationship with the state of Oregon (Portland State University, “Restructuring PSU’s Relationship with the State”; Testimony of OSU President Ed Ray to Governor’s Reset Cabinet). In November 2009, University of Oregon President Emeritus Dave Frohnmayer added his experienced voice to this debate with a thorough analysis of the factors influencing Oregon’s institutions of higher education and his own personal recommendations for change (“The Coming Crisis in College Completion: Oregon’s Challenge and Proposal for First Steps”). The State Board of Higher Education is actively engaged in these policy issues through the work of the board’s governance committee (Oregon State Board of Higher Education) And recently, The Oregonian published a letter from former State Board of Higher Education member John E. von Schlegell regarding these same issues.

At the University of Oregon, discussions about how we can better serve the state, and enhance our capacity to meet our public responsibility are well under way and include faculty members, students, staff members, alumni, and other stakeholders. We hold a collective view, joined by the University of Oregon Foundation and the University of Oregon Alumni Association Board of Directors, that the University of Oregon must continue to meet its responsibilities as a public university despite the funding environment that makes it difficult to do so. However, to accomplish this goal we need fundamental change to the governance and funding structure of our public university system. The university’s future is fundamentally predicated on our ability to enhance our capacity to provide greater educational opportunities through increased flexibility, autonomy, and stable funding support from the state.

This document adds the University of Oregon’s voice to the current policy debate about how best to accomplish these goals. It suggests a path for the University of Oregon to adopt a new public university model including new tools to stabilize funding, and it offers the possibility to think proactively about the important role our institution can play in supporting the future of our state, nation, and world.

INTRODUCTION

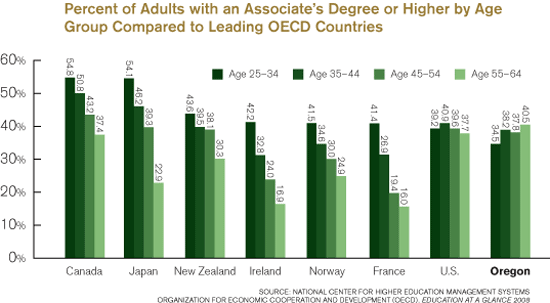

The nation, states, colleges, and universities are under great pressure to respond to economic and demographic changes. The need to respond to a “knowledge economy” is increasing at a time when international competition is intensifying and the most educated generation in American history is retiring (see Figure 1). The percentage of adults in the United States with an associate’s degree or higher compared to other countries is declining in younger age groups. These changes, coupled with limited state financial capacity, put tremendous pressure on state governments—including Oregon—to improve education at all levels.

Figure 1

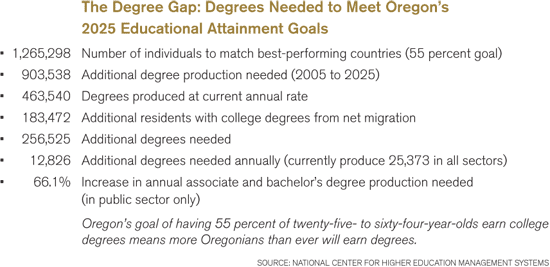

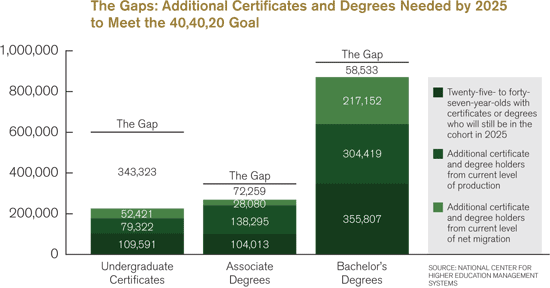

In Oregon, these conditions have created a postsecondary environment that is characterized by a deepening disparity between the educational needs of Oregonians and institutional capacity to respond. The state of Oregon is confronted with one fundamental question: How do we increase educational attainment and opportunity without significant new public investments in our public institutions? The answer to this question is likely different for each of Oregon’s seven public universities and undoubtedly requires consideration of the important role of our K–12 and community college partners. However, one point worth emphasizing: How we got here is mostly irrelevant. The question to underscore is: What are we going to do about it? Governor Kulongoski, the Joint Boards of Education, and state legislators have challenged Oregon with an ambitious goal for educational attainment (see Figures 2 and 3): by 2025, 40 percent of Oregonians will have a bachelor’s degree or higher, 40 percent will have an associate’s degree or postsecondary credential, and 20 percent will have at least a high school diploma.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Any realistic solution that addresses the challenge of increasing educational attainment in Oregon, as illustrated in Figure 3, must include enhanced institutional capacity to address the educational needs of Oregonians. We must consider alternative models that create new partnerships, and real solutions that accept that we may need to find innovative ways to increase educational attainment without significant new public investments in our public institutions. It will require new thinking about governance, accountability, and financial partnership. If we are successful, we will enhance our institution’s capacity to meet our public responsibilities and provide more Oregonians with educational opportunities.

OREGON”S PUBLIC RESPONSIBILITY AND HIGHER EDUCATION

How we respond to this challenge has very real implications. The future of our democratic society rests upon improved educational attainment for all citizens. In fact, the United States is underperforming and has lost ground in educational attainment, putting our competitive position at risk within the emerging global knowledge-based economy.

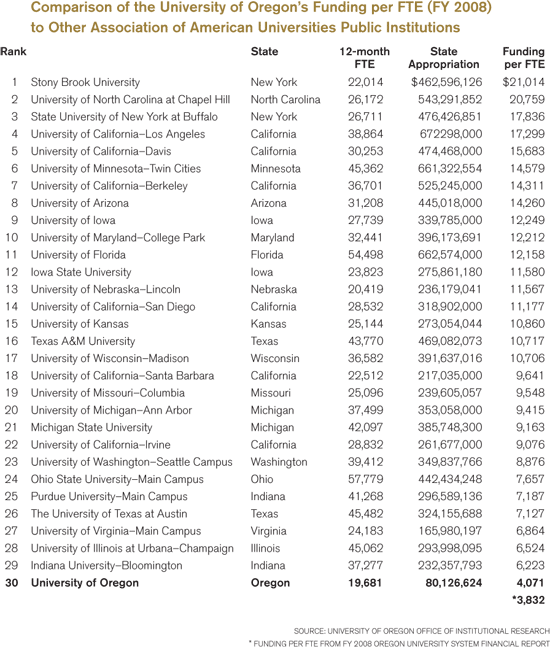

The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education underscores this point in its Measuring Up 2008 report, concluding that as other nations have invested heavily in higher education and workforce training, the United States has made little progress increasing college participation (Callan and Finney, 2008). The “national failure” to invest in higher education has created a situation where our educational strengths are heavily concentrated in the nation’s older population. Much of the rest of the world has moved in the opposite direction—educating more people at higher levels. Among the states, Oregon is at the bottom of the barrel, ranking last in many of the important criteria, including funding per student FTE, that portend Oregon’s future educational capacity and economic strength. Figure 4 compares the UO’s per-student FTE funding to other public AAU institutions.

Figure 4

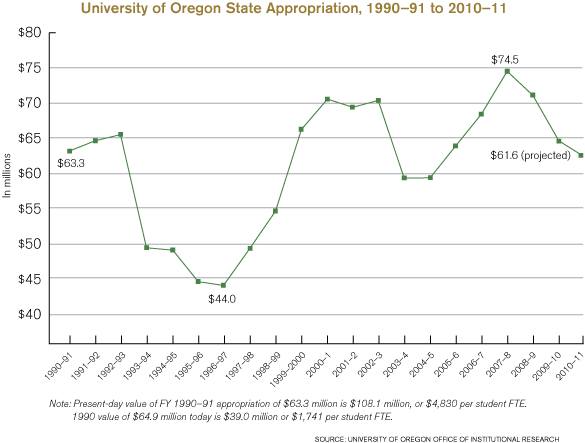

The natural cycles of state economic growth and retrenchment have created a volatile and unpredictable funding and tuition environment for Oregon’s public higher education institutions and their students over the last twenty years, and Oregon will continue to experience revenue volatility because of its dependence on income tax revenue. As a result, public higher education will inevitably face unpredictable levels of state support. This lack of fiscal predictability is embedded in the historic funding patterns of Oregon’s public higher education system, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

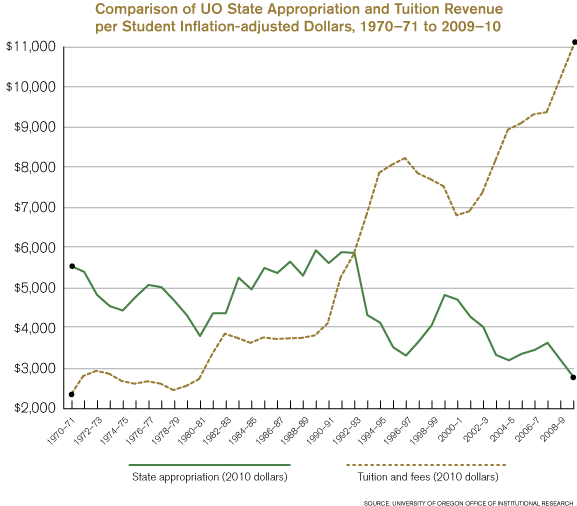

Increasing demands for public resources to finance other important state services including health care, public schools, and other mandatory services, combined with limited growth in state revenues and restrictions on taxing authority, have contributed to the state’s limited capacity to maintain or increase funding for higher education in Oregon and will continue to do so. These circumstances have contributed to a fundamental shift in the revenue streams supporting the University of Oregon. Figure 6 shows the point in time when state allocation per UO student became less than the student’s tuition.

Figure 6

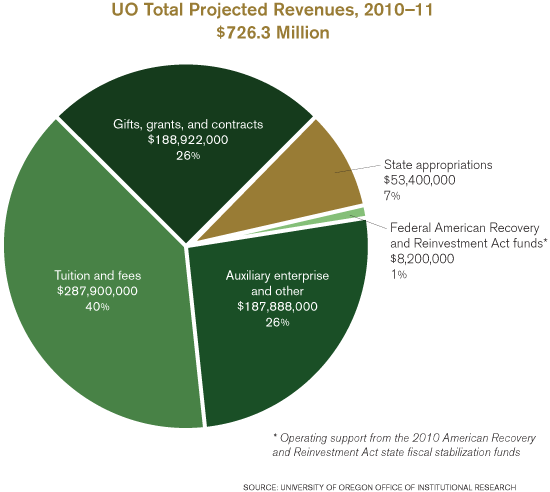

The shift in funding is most evident in the decreasing amount of state funding as a percentage of the overall institutional budget. Today, removing the federal stimulus funding, the University of Oregon receives a mere 9 percent of its overall revenues from the State of Oregon (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

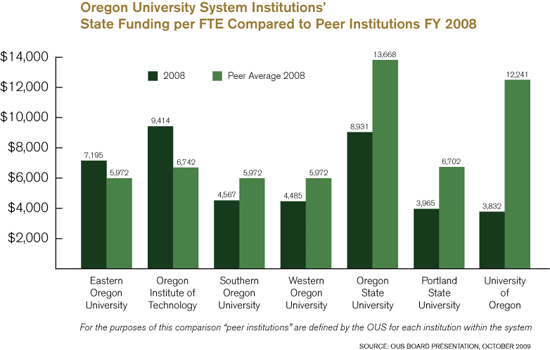

The University of Oregon is not unique in this regard, as the percentage of state funding has declined at many public flagship institutions across the country and many of these institutions, like us, have been forced to raise private revenue sources, including tuition revenue, and private gifts. Of course, our peer institutions in Oregon have experienced similar changes in their budget (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

To provide a national perspective, the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) July 2007 report, “The Evolving Relationship: Public Institutions and Their States,” stated “In 1996, 44 percent of institutions reported that state tax dollars accounted for between 50 to 100 percent of their unrestricted operating budget. A decade later, this number drops to 15 percent. No one institution reported an increase in the percentage of their operating budget supported by the state over the 10-year period” (Daulton, Shedd, and Drake, 2007, p. 3). This trend has continued and is likely to perpetuate in the future as revenue projections in Oregon forecast an estimated $2.5 billion shortfall in state revenues for the next biennium (April 2, 2010, State of the State Speech by Governor Kulongoski). It will be difficult, if not impossible, to make progress on the important goal of increasing educational attainment in this budgetary environment.

Almost inadvertently and certainly unintentionally, there has been a substantial change in the role of the state in public higher education, as the fiscal environment has profoundly changed the state’s capacity to address higher education issues. Additionally, there has been a sea change in patterns of public financing for higher education as the costs of higher education have increased and the responsibility for paying for education has slowly shifted from the taxpayers—largely in the form of state subsidies to institutions, supplemented with need-based federal aid—to individual students. The inconsistent approach to public higher education funding has been a major factor in the growing privatization of public higher education, as public institutions have become increasingly dependent on nonstate funds—predominately tuition.

The gradual shift in funding for public higher education has also served as an impetus for some states to reevaluate the campus-state relationship. Many states have engaged in renewed policy debates regarding the proper role of state government in the governance of public institutions and the accountability of institutions to meet state policy goals—seeking a balance between institutional interests to generate revenue to support the university’s mission and the state’s broader educational interests.

SETTING A NEW COURSE: AN OVERVIEW

In Oregon, we must move aggressively to enact real change that preserves our public responsibility and our ability to educate Oregonians—reform that fundamentally changes the state’s role so that each institution is better able to fulfill its public mission. The challenges and questions confronting us are:

1. How can the University of Oregon prosper, meet its public responsibility, provide a high-quality education, and help educate more Oregonians in an environment where state funding is not likely to provide the catalyst that allows us to serve the state’s needs?

2. How do we balance the dominant economic environment with the important societal mission of the university?

3. How do we balance state control and the public interest with institutional autonomy, flexibility, and accountability?

What follows is a proposal for a new public university model—a response to these questions, a response to the challenges facing the University of Oregon in its drive to meet its public responsibility and a recommendation for the University of Oregon community and our stakeholders to move aggressively to adopt a new model that provides the University of Oregon with increased autonomy to fulfill its public mission, requirements for accountability that are designed to help ensure we address the state’s needs—including increasing educational attainment, and predictable funding support from the state—a new financial partnership. The new University of Oregon public university model represents a new partnership and must include the following:

1. Governance Reform

2. Increased Accountability

3. A New Financial Partnership With the State

GOVERNANCE REFORM

There are many models of postsecondary governance in the United States. One eminent scholar on postsecondary governance structure, Aimes McGuiness, PhD, notes that there are three major types of postsecondary education governance structures: governing board states, coordinating board states, and planning-regulatory-service agency states (McGuinness, 2003). Oregon has a consolidated governing board for universities and a separate state-level coordinating board for locally governed community colleges, with no local governing boards for the four-year public institutions. There are five other states with a similar structure—Arizona, Iowa, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Wyoming (acknowledging that there is only one university in Wyoming).

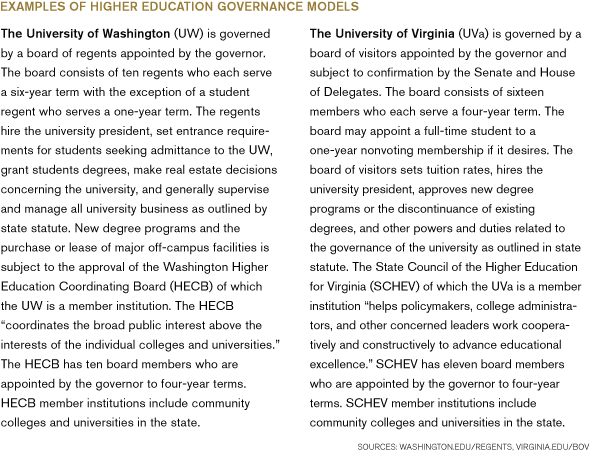

Oregon should adopt a governance structure similar to those in Virginia and Washington (see Figure 9) by establishing a state-level coordinating board for the four-year public universities, with each public university provided the opportunity to have its own public governing board. However, what works best for the University of Oregon may not work for every institution. This proposal recommends that the University of Oregon be granted an institutional governing board similar to the University of Washington. The board would be publicly appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate, would be accountable to helping ensure the University of Oregon meets its public responsibility, and focused on how the institution can thrive and prosper as it strives to provide a high-quality education. Under this model, the state coordinating board would retain the authority for degree approvals and play a critical role in ensuring the University of Oregon remains accountable to specific performance goals designed to address the state’s needs. However, all governing and budget decisions related to the University of Oregon would rest with the local campus board, similar to the authority provided to Oregon’s community colleges. The goal of governance reform, from the University of Oregon perspective, is that the University of Oregon would be granted authority for a new publicly appointed board focused on its mission and public responsibility, and the state coordinating board would become the entity focused on educational outcomes and accountability.

Figure 9

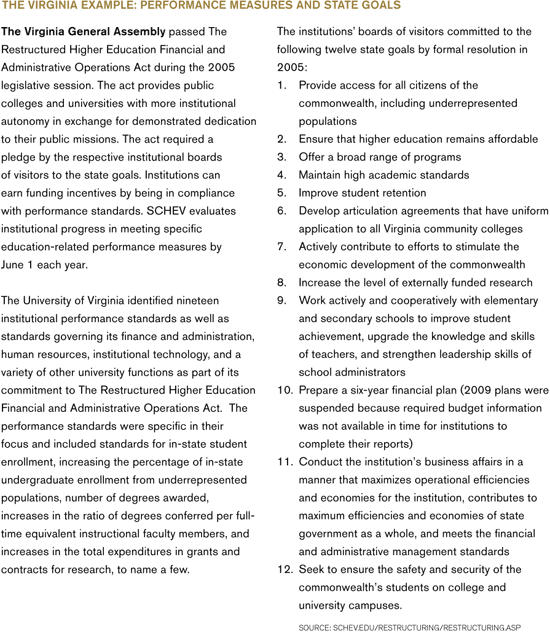

INCREASED ACCOUNTABILITY

The newly established local governing board must remain accountable to ensuring the university remains focused on its public purpose—accountable autonomy if you will. The reform of the governance system must also include some element of performance-contingent funding, providing real incentives for the institution to help address the educational attainment goals of the state. The new state-level coordinating board should set clear standards of success for the institution and hold the institution accountable for meeting those standards, such as accessibility, affordability, diversity, economic development, and service impact. Given the autonomy to fulfill our goals, we believe we can more capably deliver a high-quality education to more Oregonians, meet the goals established by the state coordinating board, and help improve Oregon’s future (see Figure 10).

Figure 10

A NEW FINANCIAL PARTNERSHIP

As previously outlined, the state’s fiscal capacity to address the critical issues of educational attainment is a grave concern. Furthermore, the challenges of operating a university with a volatile and unpredictable funding stream from the state are very difficult. Long-term fiscal and strategic planning is nearly impossible. In order to make progress on many important goals—such as increasing investments in teaching, research, and discovery; becoming more competitive for the nation’s top faculty members; and increasing student support services—we must adopt a new financial partnership, a partnership grounded in mutual accountability. We should be held accountable for delivering the educational product the state and its citizenry needs, and the state must commit to play a continuing central role in funding the educational, research, and community mission of the institution.

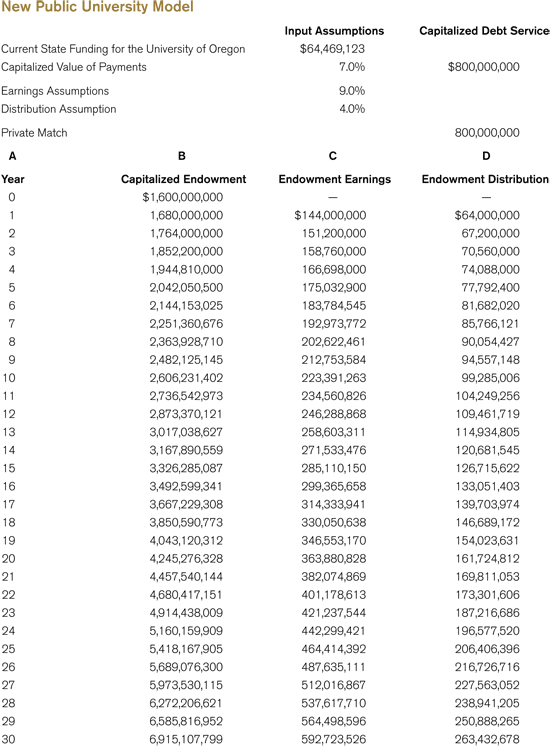

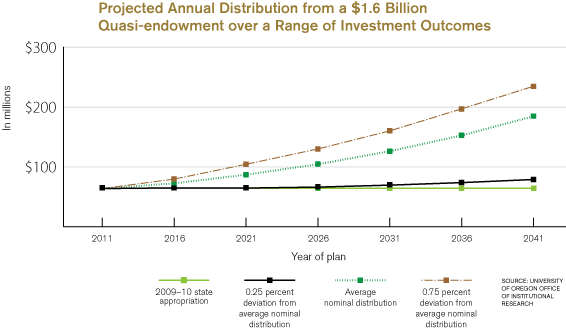

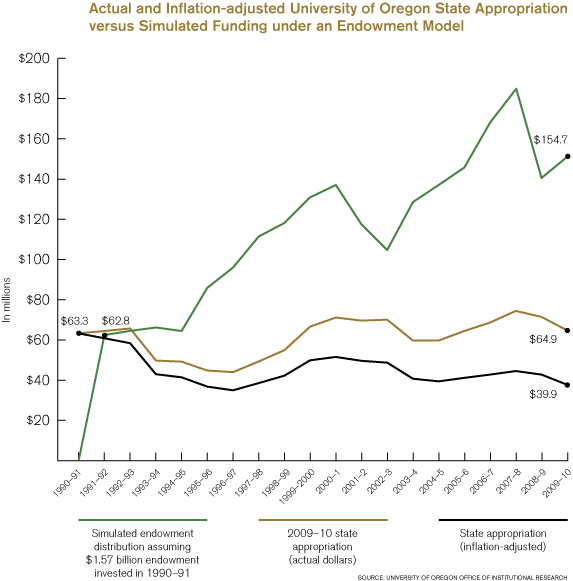

There are many ways a new financial partnership can be structured and will undoubtedly vary from university to university. The University of Oregon proposes an entirely new conceptualization for the form of the state’s funding, creating incentives for private investment in public higher education, and stabilizing the funding support provided to the institution through the creation of a public quasi-endowment (see Figures 11, 12, and 13). We propose that the state capitalize its investment in the University of Oregon and create a public endowment earmarked to fund educational opportunities for future generations of Oregonians. We would pledge to match, dollar for dollar, the state supported endowment with gift monies. For example, the University of Oregon currently receives an estimated $65 million a year in general fund support from the state and federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The University of Oregon proposes that the state appropriate these funds to support the debt issued to establish a public endowment. We would be required to match the public endowment funds with private funding. The institution would no longer submit an annual operating budget to the state, and the state’s investment in the institution would come in the form of paying off the debt issued to fund the endowment over thirty years. We believe this new financial partnership would allow the university to provide greater predictability in tuition pricing, allow the institution to engage in long-term fiscal planning, and fundamentally transform the institution’s capacity to provide a high-quality education. Moreover, while the state’s annual investment in the institution will not increase, the creation of the endowment will leverage the university’s ability to build a healthy endowment from private gifts.

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

CONCLUSION: REIMAGINING THE PUBLIC UNIVERSITY – EXCELLENCE, ACCESS, AND AFFORDABILITY

This document is intended to inspire a conversation about how best to address the critical issue of governance and public funding for the University of Oregon. It is clear action is imperative but any solution to restructure the University of Oregon’s relationship with the state must include changes to both the governance and the funding relationship. One without the other will only partially address the challenges of the contemporary environment. What is outlined here is a new partnership that creates new opportunities for private investment in the institution, provides a more stable funding structure—relieving pressure on tuition to offset state funding reductions—and alleviates the need for the state to make new investments in the institution on an annual basis. The goal for this proposal is to enhance the University of Oregon’s capacity to serve Oregonians’ educational needs. It attempts to deliver on this promise by reimagining what a public university can and should be in the twenty-first century.

The proposal, if enacted, will address three fundamental issues important to Oregonians—excellence, access, and affordability. It will enable access and affordability through greater tuition predictability for Oregonians seeking an undergraduate education. It will renew excellence by securing new private resources to invest in research, teaching, and scholarship. The new partnership allows us to reimagine what is possible at the University of Oregon under a new governance and funding relationship.

Imagine what it would mean to Oregon if our university had stable, predictable funding and the ability to plan for Oregon’s changing demographics and our state’s role in the global economy. Imagine the increased opportunities our youth will have if our university could educate more Oregonians despite the economic uncertainties of state funding. Imagine, if the state were to fund the public endowment, the university matched those funds with private gifts, and Oregonians seeking an undergraduate education at the University of Oregon were protected from inconsistent tuition fluctuations. This proposal—a reimagination of the public university—renews our capacity to serve Oregon, recommits the institution to our core public purpose, redefines how we will fund postsecondary education, restores our capacity to enhance educational excellence, and releases our full potential to fulfill our obligations as a public institution of higher education.

If we adopt public policies that stabilize financial support for the university, provide greater autonomy for the institution to operate more efficiently, create an accountability system that ensures the institution remains focused on its public responsibility, and change the governance structure, then the University of Oregon’s future and, as a result, the state’s overall prosperity will be greatly enhanced. Oregonians will see an institution poised to tackle the affordability and access question head on, and have the resources to ensure excellence in its education, research, and community service endeavors.

It is time for Oregon to once again lead the way through public policy innovation and adopt a fundamental restructuring of our public higher education financing and governance system. It is within our reach to adopt a new policy framework for higher education that realigns governance and control with a contemporary financing structure and the prevailing market forces confronting our public higher education institutions. With a stable and predictable financing structure in place, and incentives aimed at influencing institutional behavior to meet state policy goals, public higher education would no longer be driven by the economic circumstances in the state. Instead, it would be poised to more proactively and strategically meet the demands of the new global economy and Oregon’s educational attainment goals. It will be poised to tackle the access and affordability question head on, guaranteeing Oregonians undergraduate tuition stability. It will transform the University of Oregon’s capacity to deliver on its core public responsibility. Our public mission is sacred, it must be preserved, and this document has outlined a proposal to accomplish this critically important objective.

The University of Oregon is a great university, an unfinished masterpiece; together we can make it greater still. We welcome and encourage your comments.

References:

Newman, F., Couturier, L., and Scurry, J. (2004). The Future of Higher Education: Rhetoric, Reality, and the Risks of the Market. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

McLendon. (2003). State Governance Reform of Higher Education: Patterns, Trends, and Theories of the Public Policy Process. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, Vol. XVIII (pp. 57–143). London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Callan, P., and Finney, J. (2008). Measuring Up 2008: The National Report Card on Higher Education. San Jose, California: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education.

Daulton, C., Shedd, J., and Drake, M. (2007). The Evolving Relationship: Public Institutions and Their States: NACUBO.

McGuinness, A. (2003). Models of Postsecondary Education Coordination and Governance in the States. Denver: Education Commission of the States.

APPENDIX A: REVIEW OF FINANCING CONCEPT

Note: This review was authored by David Taylor and Carol Samuels, both Senior Vice Presidents of Public Finance at Seattle-Northwest Securities Corporation.

Seattle-Northwest is the largest investment bank headquartered in the Pacific Northwest and specializes in municipal finance, fixed income trading and sales and fixed income asset management.

Seattle-Northwest Securities Corporation has been engaged by Miller Nash, as counsel to the University of Oregon Foundation, to review the overall financing model put forth in the white paper entitled “Preserving Our Public Mission Through a New Partnership with the State”, dated May 14, 2010. Specifically, we have been asked to comment as to the soundness of the general theory underlying the model, the ability of the State of Oregon to effectively market the related bonds, the potential impact on the State’s debt capacity and bond rating, and the completeness of the model’s assumptions. We have not undertaken to independently verify the reasonableness of the assumptions.

Overall Theory. We find that the overall theory of replacing a biennial general fund appropriation with a capitalized endowment fund is functionally sound. The long term financial success of the proposed plan rests on the following key factors: a) the interest rates obtainable for the bond issue; b) the University’s ability to leverage new private donations in like amount that would not otherwise be available under the status quo; c) the endowment’s long term rate of return; and d) the University’s endowment spending policy.

The proposed model replaces an uncertain resource that is dependent on the legislative appropriation process with a likely more predictable resource within the University’s control. While it is impossible to conclude that the proposed plan will ultimately provide greater resources to the University than the status quo (the future level of general fund appropriations being unknowable), assuming the variables in the model prove accurate, it should provide for greater certainty for both the University and State budgets. Further, by producing a ‘matching’ base against which private donors may be enticed to contribute, the proposed plan may successfully leverage State dollars in a way not currently achievable, providing significant new investment in the public mission of the University from private dollars.

Marketability. Absent some significant change in the State of Oregon’s credit or in market conditions, we believe the State could sell the amount of bonds assumed in the model as a taxable general obligation bond and receive broad market acceptance and competitive interest rates. As general obligations of the State, the proposed security is the strongest credit the State may offer. Although the additional debt burden may give market participants some concern, the annual increase in debt service is not significant relative to the overall size of the State’s budget. We note the State has previously been successful in marketing taxable bonds of even greater amount (the 2003 Pension Obligations were sold in the amount of $2 billion). The taxable municipal market has since improved in liquidity and marketability with the growth of the Build America Bond program. However, to the extent that the introduction of this borrowing program coincides with a significant increase in the overall debt level of the State of Oregon generally, lenders may have a more negative view of this borrowing.

Impact on State Debt Capacity and Rating. The issuance of taxable general obligation debt in the amount estimated in the model can be managed within the State’s current debt capacity guidelines and ratings expectation. Because debt capacity is limited under current policies, however, implementing the proposed financing plan will either require tradeoffs in the timing and size of other competing projects or revision of current policy guidelines.

Debt capacity policy is generally proposed by the State Debt Policy Advisory Commission and usually accepted by the Legislature as policy guidelines. The most recent report of the commission (February 1, 2010) identifies approximately $2.7 billion in general fund supported capacity over the next two biennia (i.e. through FY 2015). The report also suggests that this capacity should be committed to a “considerable backlog of high priority projects”. As with any limited resource, the State will need to either prioritize policy choices or modify the terms under which the resource is utilized. For example, to the extent the debt service on this proposal can be considered as a ‘replacement’ obligation, i.e., an obligation that the State is already committed to, but in a different form, it is possible to minimize its impact on “capacity”.

For an issue of this type, rating agencies will likely focus on the effect of converting a “soft” liability (the commitment to fund a portion of annual operations for the University of Oregon) to a fixed “hard” liability (debt service on the bonds). In ratings terms, this would likely be viewed as decreasing the State’s financial flexibility, albeit at the margin. We have engaged in several general conversations with rating analysts at Moody’s and S&P that confirm this view. However, given the expected debt service relative to the State’s budget, the analysts did not believe this borrowing, by itself, would be likely to affect the State’s overall rating.

Model Assumptions. We have been asked to review the proposed financing model for its inclusiveness of all relevant assumptions. We find that the model does include all relevant assumptions to make the model a reasonable financing tool. We express no opinion about the reasonableness of the assumptions themselves.

Conclusions. We believe the proposed financing model includes all relevant assumptions and can be used as a policy informing tool. In addition, we believe the proposed amount of State of Oregon taxable general obligation debt is saleable at reasonable market prices and that, by itself, such a debt issue should not negatively affect the State’s general obligation bond rating. Such an issue, if sold in the next several biennia, would almost certainly require some revision of State debt policy or a delay in financing of other State projects.

APPENDIX B: LEGISLATIVE OUTLINE OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY CONCEPT

Note: The following was prepared for the University of Oregon Foundation by Jeffrey G. Condit from Miller Nash, Attorneys at Law.

I. INTRODUCTION

This is an outline of the final Legislative Counsel (“LC”) drafts of the University of Oregon Foundation’s “New Partnership with Oregon” legislation.

II. LC 1751 (GOVERNANCE)

A. General Provisions.

1. Section 1: The New Public University Model. The concept creates the University of Oregon (“UO”) as a “public university” and grants it general independent powers similar to other independent public bodies. The UO would continue to be a governmental body of the State of Oregon, but it would be governed by its own Board of Directors rather than by the State Board of Higher Education.

2. Section 2: Powers Clause; Public University as Template. The concept grants to the UO “authority over all matters of university concern,” similar to the statutory home rule grant to cities and counties. The intent is to grant to the UO all express and implied powers necessary to carry out its public mission so that it has the legal flexibility to meet its needs and address changing conditions. The section also states the bill’s intent that the “public university” concept serve as a template for other institutions of higher education in the Oregon University System (“OUS”) as they become ready for self-governance.

3. Section 3: Mission and Goals. This section sets forth the UO’s mission and defines “matters of university concern.” This includes the provision of high-quality higher education, research, economic development, the preservation and dissemination of information and culture, and the development of new knowledge as key parts of the university’s mission.

B. University of Oregon Board of Directors.

1. Section 4: Membership/Operations.

a. Board Created. The proposed Board includes 15 members, as follows:

(i) Seven members appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate, including:

(A) One member who is a UO student in good standing; and

(B) One member of the UO faculty.

(ii) One non-student member of the State Board of Higher Education, appointed by the Board of Higher Education.

(iii) Six members appointed by the University of Oregon Board of Directors, including:

(A) One member of the University of Oregon Foundation Board of Directors, appointed in consultation with the Foundation Board.

(B) Five at-large members.

(iv) The president of the university, in an ex-officio non-voting capacity.

(v) Additional non-voting members appointed by the Board as the Board deems necessary or beneficial.

b. Term of Office. Four years; two years for the student member, with a two-term limit.

c. Board Governance. The Board would appoint the chair and adopt bylaws for its operations.

2. Sections 5 and 6: First Board. These sections are transition provisions providing for the initial appointment of the Board and the staggering of terms.

3. Section 7: Powers and Duties of the Board. The concept vests all powers in the Board of Directors or to officials as delegated by the Board. Powers include the power to enact policies that have the force of law, hire employees, execute contracts, borrow money and issue debt, acquire or sell real and personal property, sue and be sued, construct buildings, set tuition and fees, and such other actions over matters of university concern.

4. Section 8: President of the University. This section establishes the office of president and provides that the president is the president of the faculty and the chief executive officer of the university, subject to the rules of the Board. This is essentially the same as the current provision in the OUS statute, with the exception that the UO Board of Directors, not the State Board, will appoint and have direction over the president.

C. Authority and Duties of Public University.

1. Section 9: Exemptions/Compliance with Laws Applicable to State Agencies. The UO would continue to be subject to what I refer to as the public governance provisions of state law: The Public Records and Meetings Law, Government Ethics, Investment of Public Funds, the Public Employees Collective Bargaining Act, Public Retirement, and the Oregon Tort Claims Act. But the UO would be exempted from many of the business regulations applicable to state agencies, such as the Administrative Procedures Act. The new UO Board would also take control of those business matters currently managed by the State Board of Higher Education or other state agencies, such as property acquisition and sale, rule making, collective bargaining (but see Section 10, below), and management and control of UO finances, including the setting and collection of tuition. This section is substantially similar to the equivalent grant of authority in the OHSU statute.

2. Section 10: Continuation of PEBB and State Collective Bargaining in Certain Circumstances. Notwithstanding the exemptions in Section 9, participation in the Public Employees Benefit Board benefits and new collective bargaining agreements negotiated by the state for OUS employees would continue to apply to the UO unless and until the university’s represented employees choose to negotiate a different benefit package or separate collective bargaining agreement.

3. Section 11: Individuals with Disabilities. Incorporates the same statutory requirement applicable to OUS and OHSU regarding contracting with qualified nonprofit agencies for individuals with disabilities.

4. Section 12: Report to Legislature. Requires a report of activities to the legislature similar to the report required of OHSU.

5. Section 13: University Property. Title to property currently used by or managed for the benefit of the university would remain with the State of Oregon. Authority to buy, sell, or otherwise manage this property is transferred to the UO Board of Directors. (Currently, such decisions are made by the State Board of Higher Education.) Property acquired by the university after the effective date of the Public University model would be acquired in the name of the university.

6. Section 14: Timber/Mineral Rights. Grants to the UO Board the same powers to sell timber and mineral rights on UO property as the State Board currently enjoys on OUS property.

7. Section 15: Eminent Domain. Grants the UO Board the power to condemn property for UO use, consistent with the current authority of the State Board and the OHSU Board.

8. Section 16: Required Alcohol and Drug Policy. Incorporates the current OUS and OHSU statutory mandate to adopt a comprehensive drug and alcohol abuse policy. This mandate currently applies to all OUS institutions.

9. Section 17: Public Contracts. Authorizes the UO Board to adopt public contracting rules for the UO consistent with overall policy of the Public Contracting Code.

10. Section 18: Funding Request/Exemption from Expenditure Limitation. Establishes deadline for filing funding requests with the legislature, consistent with the OHSU requirement. Expressly exempts UO from having to seek expenditure limitation approval from the legislature to expend available funds.

11. Section 19: Audits. Recognizes the Secretary of State’s continuing authority to conduct audits of the UO, but provides that the UO Board may also conduct its own audits.

12. Section 20: Campus Police. Grants authority to the UO Board to establish a campus police force consistent with the authority currently granted to the State Board of Higher Education.

13. Section 21: Traffic Control. Grants authority to the UO Board to adopt parking and traffic control regulations consistent with the authority granted to the State Board.

14. Section 22: Criminal Records Checks. Grants authority to the UO Board to require criminal records checks of employees and contractors consistent with the authority granted to the State Board.

15. Section 23: Streets/Sidewalks. Incorporates the UO’s current statutory authority to construct and dedicate streets and sidewalks into the UO statute. Creates UO as the road authority for streets through lands owned or used for the university.

D. Students.

1. Sections 24 through 29: Incorporation of Existing Requirements Relating to Students. These sections incorporate statutory provisions currently applicable to OUS institutions relating to students, including student records, non-discrimination on the basis of non-attendance for religious reasons, and certain rights, credits, exemptions, and tuition breaks for students called away for military service.

2. Section 30. Physical Access Committee. Section 30 incorporates provisions currently applicable to OUS and OHSU relating to creation of a physical access committee.

E. Personnel.

1. Section 31: Alternative Retirement Program. This section authorizes the UO to offer its employees, in addition to the Public Employees Retirement System (“PERS”), alternative retirement programs. This is consistent with the same authority granted to OHSU.

2. Sections 32 through 36: Incorporation of Current OUS Personnel Regulations. These sections incorporate provisions relating to personnel in the current OUS statute into the proposed UO statute. These sections include regulations governing UO personnel records; authorizing staff to accept compensation from third parties for consulting, speeches, intellectual property, or other efforts; a description of the role and authority of the president and faculty consistent with the original university charter language in the OUS statute; a requirement for affirmative action during any reduction in force; and the prohibition against any political or sectarian test for faculty appointments.

F. Finance.

1. Section 37: Existing Debt Obligations of the State. Provides that nothing in the new UO statute will impair existing debt or other financial obligations of the state incurred on behalf of the UO.

2. Sections 38 through 40: Revenue Bonds. Authorizes the UO Board to issue revenue bonds and refunding bonds.

3. Section 41: Notice of Shortfall. Requires UO to notify the legislative assembly or emergency board of any shortfall of moneys to repay any debt incurred by the state on the UO’s behalf prior to the effective date of the new UO statute.

4. Sections 42 and 43: XI-F and XI-G Bonds. Authorizes the UO Board to request the State Treasurer to issue bonds for capital projects as authorized by Articles XI-F and XI-G of the Oregon Constitution. This is the same authority as is currently exercised by the State Board of Higher Education.

5. Section 44: Endowment Bond Placeholder. This provision implements the endowment bond established in LC 1761, if approved by the voters.

6. Sections 45 through 49: Financing/Credit Agreements. Authorizes the UO Board to enter into financing and credit agreements, similar to the authority granted to OHSU.

7. Section 50: Authorization for UO to Accept Donations.

G. Programs.

1. Section 51: Role of Oregon University System; Benchmarks. Retains current State Board of Higher Education authority over coordination and approval of degree programs. This portion is similar to the relationship between the State Board and OHSU in the OHSU statute. The major difference is that this section also authorizes the State Board to adopt benchmarks to ensure that the UO delivers an education program that will meet the state’s higher education needs and goals. The purpose of the benchmarks is to provide for a new method of state oversight in return for the increased operational autonomy. The hope is to focus on the outcomes that the state desires from the UO. The provision emphasizes that the benchmarks are to be outcome-based, with the means and methods of meeting those benchmarks left up to the UO, and provides that the State Board may also adopt incentives for achieving the benchmarks and penalties for failure to meet them.

2. Sections 52: Venture Grant. This section incorporates certain existing UO program statutes from the OUS statute into to the UO statute.

H. Transition Provisions. Sections 53 through 64 contain the transition provisions to implement the change in governance structure. They are very similar to the transition provisions in the OHSU enabling act.

1. Section 53: Definitions Applicable to the Transition Sections. Defines the UO under the current structure as the “former university,” and defines it as the “university” under its new authority.

2. Section 54: Transfer of Personnel, Labor Agreements. Transfers all personnel of the former university to the new university retaining all salary, benefits, contracts, seniority, and tenure. Transfers all collective bargaining agreements to the new university and retains all representation rights of current collective bargaining organizations. (As described above, Section 10 provides that subsequent OUS collective bargaining agreements would continue to apply to UO unless and until the UO and its represented employees elect to negotiate a separate collective bargaining agreement.)

3. Section 55: Transfer of Duties. Transfers all duties of former university officials to university officials.

4. Section 56: Records and Property. Transfers all records and personal property from the former university to the university. Transfers control of all real property used or managed for the benefit of the former university to the university.

5. Section 57: Appropriations. Transfers all appropriations of funds to the former university to the new university.

6. Section 58: Legal Obligations. Transfers all legal obligations or actions to the new university.

7. Section 59: Penalties and Forfeitures. Transfers all penalties and forfeiture obligations to the new university.

8. Section 60: Continuity of Legal Entity. Clarifies that the university is considered a continuation of the former university for the purpose of succession to all rights, obligations, duties, functions, and powers.

9. Section 61: Administrative Rules. Transfers all current OUS administrative rules applicable to the former university to the new university until amended or repealed by the UO Board of Directors.

10. Section 62: Moneys, Payroll. Transfers moneys and payroll of the former university to the new university.

11. Section 63: Contracts. Transfers State Board of Higher Education rights and obligations under contracts with regard to the former university to the UO Board of Directors.

12. Section 64: Payment Obligations. Transfers the State Board’s authority to expend funds and pay on obligations to the UO Board of Directors.

I. Public Records. Sections 65 and 66 amend ORS 192.502 and ORS 192.690 to grant records/meetings exemptions for sensitive business records and records regarding candidates for president, mirroring exemptions granted to OHSU.

J. Conforming Amendments. Sections 67 through 178 make conforming amendments to a myriad of current statutes to reflect the UO’s status as a new public university and to maintain existing university authority, obligations, or benefits.

K. Implementation Amendments.

1. Section 179: Repeals ORS 352.035 (State Board authority over UO streets).

2. Section 181: Relocated Statutes. This section relocates certain provisions relating to UO that were formerly in the OUS statutes (ORS Chapters 351 and 352) into the new UO statute.

3. Section 180, 182: Effective Date. These sections establish the effective date of July 1, 2011, with full transition occurring on January 1, 2012.

III. LC 1761 (ENDOWMENT)

A. Structure. LC 1761 is a Joint Resolution to refer a constitutional amendment to the voters to authorize the state to issue bonds to help establish an endowment fund at the request of a public university. A constitutional amendment is necessary because the state’s authority to incur debt is otherwise constitutionally limited. Similar constitutional amendments have been referred to and approved by the voters many times in the past to allow the state to issue debt for a variety of public purposes, from building public infrastructure to financing PERS pension liabilities. See Oregon Constitution, Articles XI-A through XI-O.

B. Section 1 (Authority for and Structure of Endowment Fund).

1. Paragraphs 1 and 8 (Authority to Issue Debt to Create University Endowment). Creates exception to the state’s constitutional debt limitation to allow the state to fund endowment funds for public universities in Oregon and pledge the state’s full faith and credit.

2. Paragraphs 2 and 3 (Amount of Debt, Cap). Authorizes the state to incur indebtedness up to $1 billion at the request of a public university to fund an endowment fund for the public university. Caps the indebtedness that may be incurred to $1 billion for each public university.

3. Paragraph 4 (Management of Endowment). Empowers a public university to manage the endowment fund itself or transfer it to an affiliated foundation to manage for the benefit of the university.

4. Paragraph 5 (Limitation on Use of Endowment Funds). Limits use of the endowment fund for the operation of the public university and the benefit of its students.

5. Paragraph 6 (Local Matching Funds Required). Conditions the state’s obligation to issue debt on demonstration by a public university that it has raised matching funds from contributions or other sources for the endowment at least equal to the amount of debt to be incurred by the state.

6. Paragraph 7 (Bond Issues Can Be Staggered as Funds are Raised or as Necessary to Manage State’s Debt Capacity). Allows the treasurer to issue bonds over time as funds are raised or as necessary to manage the debt capacity of the state.

C. Section 2 (Authorizes Issuance of Refunding Bonds). Allows the state to issue debt to refinance a bond issue under this section. This would allow the state to take advantage of lower interest rates during the life of the bonds.

D. Section 3 (Payment of Bonds). Identifies sources of state revenue to pay the bonds.

E. Section 4 (Definition of “Public University”). Defines “public university” as an institution of higher education within the Oregon University System or an independent public corporation in the state of Oregon that provides higher education. This definition would enable the University of Oregon to request the bonds under this Act regardless of whether LC 1751 is enacted creating UO as an independent public university or whether it remains part of OUS. It would also allow the other OUS institutions and OHSU to request creation of an endowment under this Act.

F. Section 5 (Empowers Legislature to Enact Implementing Legislation) and Section 6 (Supersedes Conflicting Constitutional Provisions). These are standard implementing provisions for such amendments.

IV. CONCLUSION

This is a very exciting project that will be transformative for higher education in Oregon. We are pleased and proud to be a part of your efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

On behalf of the University of Oregon, I sincerely thank the many contributors to this project, particularly the University of Oregon Foundation trustees and the University of Oregon Alumni Association board for their support and insistence that the University of Oregon put forth a plan for preserving the University of Oregon’s public mission.

Through the financial support of the University of Oregon Foundation, this project benefitted enormously from the services provided by attorney Jeffrey Condit of Miller Nash and by Carol Samuels and David Taylor of Seattle-Northwest Securities Corporation.

I’m especially grateful to Michael Redding, EdD, vice president for university relations.

Important contributors to this project include:

• John Chalmers, PhD, Abbott Keller Distinguished Research Scholar, associate professor of finance

• J.P. Monroe, PhD, director of institutional research

• Jay Namyet, chief investment officer, University of Oregon Foundation

• The dedicated staff members of the Office of Public and Government Affairs under the skilled guidance of Betsy Boyd, particularly Government and Community Relations, Design and Editing Services, and Web Communications.

—Richard W. Lariviere